New DISBench study reveals why top AI models fail at personal photo retrieval

New evaluations reveal why advanced AI fails at complex retrieval, exposing the gap between generative art and contextual reasoning.

February 22, 2026

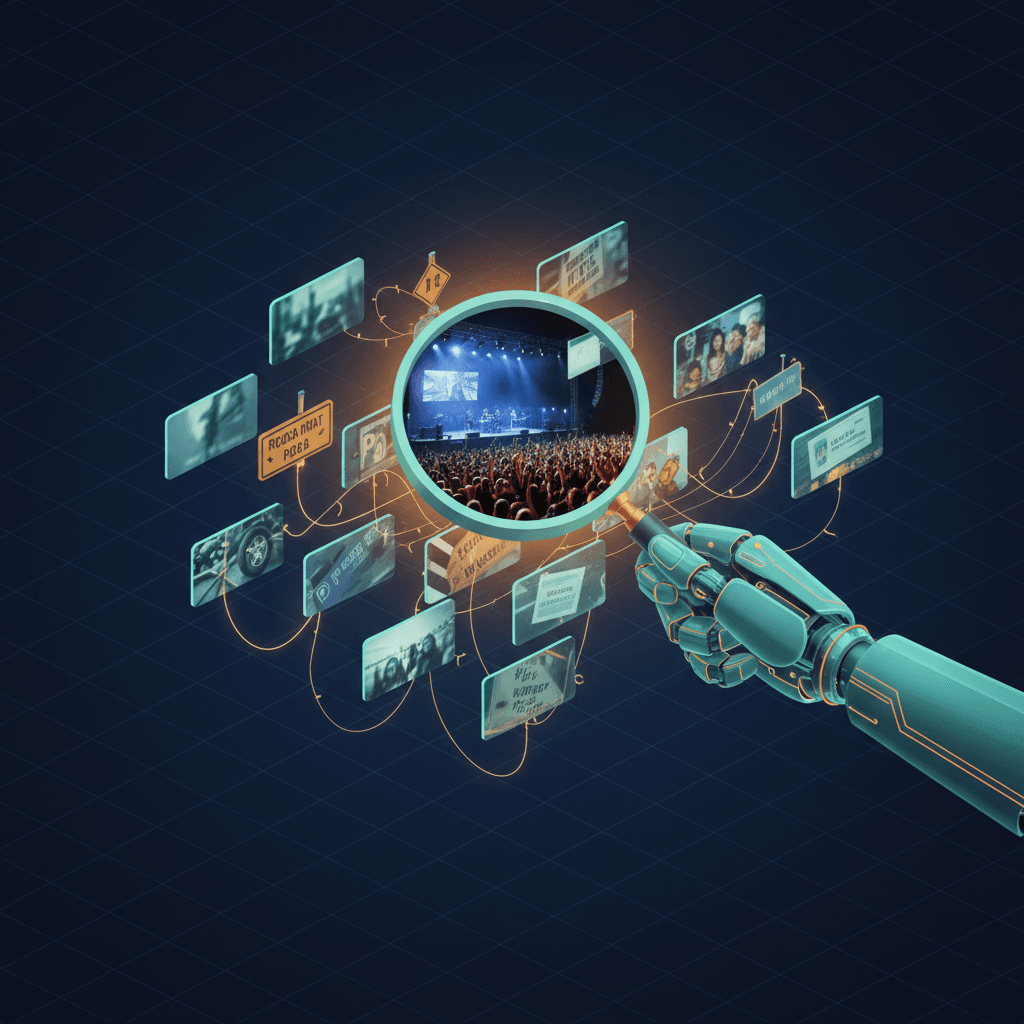

The current era of artificial intelligence is defined by a striking paradox: while a model can generate a photorealistic portrait of a seventeenth-century astronaut or compose a symphony in seconds, it often remains helplessly lost when asked to find a specific photo of a concert ticket buried in a user’s personal gallery. This gap between generative brilliance and retrieval failure has been highlighted by a rigorous new evaluation framework known as DISBench.[1] Developed by researchers from Renmin University of China and the Oppo Research Institute, the benchmark reveals that even the most advanced multimodal models, including high-end systems like Nano Banana Pro and Claude 4.5, struggle significantly with the nuances of personal image retrieval.[1] The findings are a sobering reminder that "seeing" an image is fundamentally different from "understanding" the messy, interconnected context of a human life.

At the heart of the problem is the complexity of how humans remember and search. Most existing AI photo tools rely on simple object recognition—identifying "cat," "beach," or "concert." However, human queries are rarely so straightforward. We often look for photos using a chain of contextual clues: "find the photo of the lead singer from that show where the entrance had a blue and white logo."[1] To solve this, an AI cannot simply look for a singer; it must first identify which concert the user is referring to by finding a different photo of the entrance, extract the relevant information, and then apply that specific context to find the target image. DISBench specifically tests this "agentic" ability to reason across multiple images in a collection. The results were remarkably low, with the top-performing models correctly identifying the full set of relevant images in only about 29 percent of test cases.[1]

The failure is not primarily a matter of computer vision.[2][3][4] Modern models are excellent at identifying individual objects or reading text within a single frame. Instead, the research identifies "planning ability" as the primary bottleneck. Approximately 50 percent of all errors in the benchmark stemmed from models correctly identifying the initial context but then failing to follow through on the search constraints.[1] In many instances, the AI would find one correct image and then stop the search prematurely, or it would lose track of the specific requirements as it navigated the gallery.[1] This suggests that while AI can "see" perfectly well, it cannot yet "plan" a multi-step investigation of a personal database.[1] It lacks the persistence and logical consistency required to mimic the way a human mind sifts through memories to find a needle in a haystack.

Another significant technical hurdle is a phenomenon known as "semantic override" or "concept bleed."[5] Because high-end models like Nano Banana Pro are trained on vast amounts of world knowledge, they often develop a "thinking" bias that prioritizes general concepts over specific, low-fidelity visual evidence. For example, if a user asks for a photo of a specific local musician at a small club, the AI might accidentally prioritize its internal knowledge of what a "famous concert" looks like, ignoring the specific, perhaps blurry or poorly lit, details of the user’s actual photo. This creates a situation where a "smarter" model can actually perform worse at personal retrieval than a "dumber" model, because the advanced model is too busy trying to interpret the scene through the lens of its training data rather than sticking to the raw pixels of the private collection.[5]

The implications for the smartphone and cloud storage industries are profound. Tech giants like Apple, Google, and Oppo have spent years marketing "AI-powered" galleries, yet the DISBench results suggest that current consumer-grade search is only marginally better than random chance when faced with complex, multi-image queries. For a truly useful AI assistant to emerge, the industry must move beyond "generative AI" and toward "retrieval-augmented reasoning." This would involve models that can build a temporary mental map of a user's entire gallery, understanding that a photo of a restaurant menu taken at noon is logically linked to a blurry photo of a dinner plate taken three hours later. Without this temporal and spatial awareness, AI search remains a blunt instrument that succeeds only when the user provides the exact keyword the algorithm expects.

Furthermore, the transition to local, on-device AI adds a layer of hardware-based difficulty. While cloud-based models have the computational power to index every detail of a photo, they are often restricted by privacy regulations and the massive bandwidth costs of constant server communication. On-device chips, or Neural Processing Units, are becoming more powerful, but they still struggle to run the massive multimodal models required for the deep reasoning shown in the DISBench study. This creates a "privacy-performance" trade-off: users want the intelligent search capabilities of a model like Claude 4.5, but they are increasingly hesitant to upload their entire personal history to a corporate server where that reasoning takes place. Bridging this gap requires a new class of efficient, "agentic" models that can perform complex planning and cross-referencing within the thermal and power constraints of a handheld device.

The "modal aphasia" identified in recent research also plays a role in these search failures. This term refers to a fundamental disconnect where a model can recall information through one modality, such as generating an image, but cannot access that same information through language-based reasoning.[2] In the context of a photo gallery, an AI might be able to "describe" every image in a folder perfectly, but when asked to "find the photo that explains why I was late to the concert," it fails to make the logical leap to the photo of the flat tire taken earlier that day. The information is present in the visual data, but the model cannot translate that visual "memory" into a linguistic solution for the search query.

As the AI industry matures, the focus is likely to shift from the novelty of image generation to the utility of image retrieval. The "sobering" results of recent benchmarks act as a necessary course correction for an industry that has perhaps become over-reliant on the "magic" of generative models while neglecting the structural logic of data management. The next generation of AI assistants will need to be more than just artists or writers; they will need to be digital detectives. They must be capable of maintaining a "state" of search, holding multiple constraints in their memory, and navigating the messy, unlabelled, and often low-quality world of personal photography with the same rigor a human uses to navigate their own past.

Ultimately, the reason AI still cannot find that one elusive concert photo is that it doesn't yet understand what a "concert" means to the person who attended it. To a machine, a concert is a collection of labels like "person," "microphone," and "stage lights." To a human, a concert is a sequence of events starting from the ticket purchase and ending with the blurry walk to the parking lot. Until AI models can replicate this sequential, causal understanding of life, our digital galleries will remain vast, unsearchable warehouses of data. The path forward lies in improving the planning and reasoning layers of multimodal AI, ensuring that the next time a user asks for a memory, the machine doesn't just look at the pixels, but follows the story.