US Sets Monumental Goal: Quadruple Nuclear Power to Fuel Global AI Race

Quadrupling capacity to fuel the AI revolution relies on an aggressive SMR gamble and overcoming the costly legacy of reactor failures.

January 10, 2026

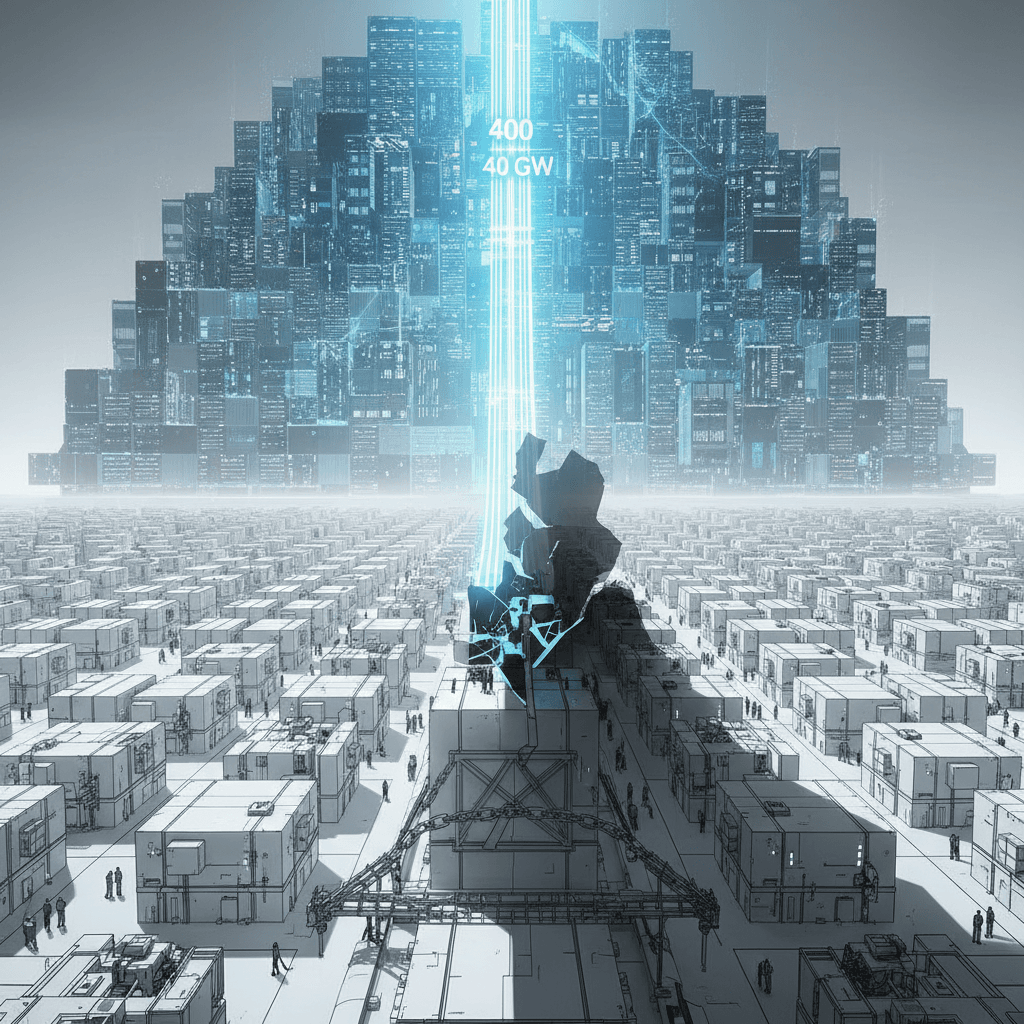

The United States is embarking on an unprecedented, ambitious energy goal to quadruple its nuclear power capacity by 2050, a strategy driven largely by the exploding, unyielding electricity demands of the artificial intelligence industry. The White House, citing national security and the global race for AI dominance, has set a target to increase nuclear capacity from its current level of approximately 100 gigawatts (GW) to 400 GW, a goal that would require a monumental, sustained build-out surpassing the peak construction era of the 1970s. This aggressive push is a direct response to the massive energy needs of AI data centers, which are projected to more than double their electricity consumption by 2030, a surge equivalent to the annual power demand of entire mid-sized nations. Major technology firms like Microsoft, Google, and Amazon have already signaled their support by signing long-term power purchase agreements and investing in nuclear projects, including the revival of shuttered power plants and the development of next-generation reactor designs, demonstrating a clear private sector belief that nuclear power is the most reliable, round-the-clock, carbon-free source to fuel the AI revolution.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

The specter of past financial and logistical failures, however, casts a long shadow over the current nuclear renaissance plan, raising widespread skepticism from market experts and industry insiders. The historical record of large-scale reactor construction in the U.S. is marred by colossal cost overruns and years of delays, most notably with the recent expansion project at Plant Vogtle in Georgia. The two new reactors at Vogtle, which began commercial operations, came online seven years behind schedule and incurred a budget overrun of an estimated $18 billion.[10][7] Construction costs at Vogtle soared to approximately $15,000 per kilowatt, a staggering five times the cost of comparable projects in South Korea.[7] This cautionary tale, known as the "Vogtle Legacy Issue," has made utility companies and private investors wary of committing substantial capital to new, traditional large-scale nuclear builds without significant federal guarantees against financial risks. As a result, only three nuclear reactors have been completed in the U.S. since the 1990s, with none currently under construction, leaving the industry's focus centered on extending the operational licenses of the existing fleet of 94 reactors or attempting to restart recently retired units.[11][12][8]

The current strategy for achieving the quadrupling goal leans heavily on the successful, rapid deployment of Small Modular Reactors, or SMRs, and microreactors, which are touted as the key to overcoming the industry's historical challenges. These advanced nuclear technologies are designed to be factory-fabricated, standardized, and transported to the site, theoretically lowering capital costs and speeding up installation time, a major selling point for powering concentrated, energy-hungry AI data centers. Tech giants are among the key corporate backers of SMR development, with some planning to finance more than 20 GW of SMR capacity.[3][13][14][15] However, SMRs face their own significant "hype-versus-reality" gap, as the technology remains largely unproven at a commercial scale in the U.S.[10][15][6] Of the more than 50 SMR designs currently under development, none has yet received an operating license from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), and the industry's first planned commercial SMR project, led by NuScale Power, was canceled due to spiraling costs and a lack of subscribers. Furthermore, while the government has issued executive orders to dramatically speed up the licensing process, mandating a decision on new reactor applications within 18 months, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, an independent agency, must manage this streamlined timeline while ensuring the highest level of public safety and regulatory rigor.[16][1][6][8] The ramp-up is projected to be slow, with some analyses forecasting that widespread SMR adoption will not begin until after 2035, leaving a critical decade-long gap between the surging AI power demand and the nuclear supply.[15][6]

Beyond the technological and financial hurdles, the plan confronts major constraints across the entire nuclear supply chain and workforce. To triple the nation's nuclear capacity, the Department of Energy estimates the country would need an additional 375,000 workers, a massive labor force mobilization that requires years of specialized training.[8] Furthermore, the domestic nuclear fuel cycle infrastructure has atrophied, leaving the U.S. heavily dependent on foreign sources for essential materials like uranium, enrichment, and conversion services.[2][8] Executive orders have been signed to mandate the expansion of domestic uranium conversion and enrichment capacity to meet civilian and defense needs, but rebuilding this complex industrial base will take considerable time and investment.[16][2] The sheer scale of the 400 GW target would require the U.S. to commission an average of 15 GW of new nuclear capacity annually from 2030 to 2050, a rate that surpasses the peak commissioning rate of 10.5 GW set in 1974.[7][8] Meeting this aggressive schedule, critics argue, is "absolutely unattainable" without first dismantling the core barriers of high cost, lengthy construction timelines, and regulatory complexity that have historically crippled the industry.[7][8] The outcome of this effort will not only determine the future of US energy policy but will also be a major factor in the global race for dominance in artificial intelligence, where reliable, immense power is now the primary competitive bottleneck.[2][4][7]

Sources

[1]

[4]

[7]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]