Rigorous Science Benchmark Reveals Deep Limits of AI Reasoning

New benchmark demonstrates high-scoring AI models fail at the critical, iterative tasks of real scientific discovery.

December 26, 2025

The ambition of developing a fully autonomous AI researcher—a language model capable of driving fundamental scientific discovery from hypothesis to validated result—has been one of the most compelling narratives in the technology industry. Yet, a new, rigorously designed benchmark offers a sobering reality check, demonstrating that the celebrated intelligence of large language models remains profoundly limited when faced with the messy, iterative demands of real-world research. The study, conducted by an international consortium of more than thirty researchers from leading institutions including Cornell, MIT, Stanford, and Cambridge, reveals a significant chasm between a model's ability to ace academic-style exams and its capacity for genuine scientific thinking.

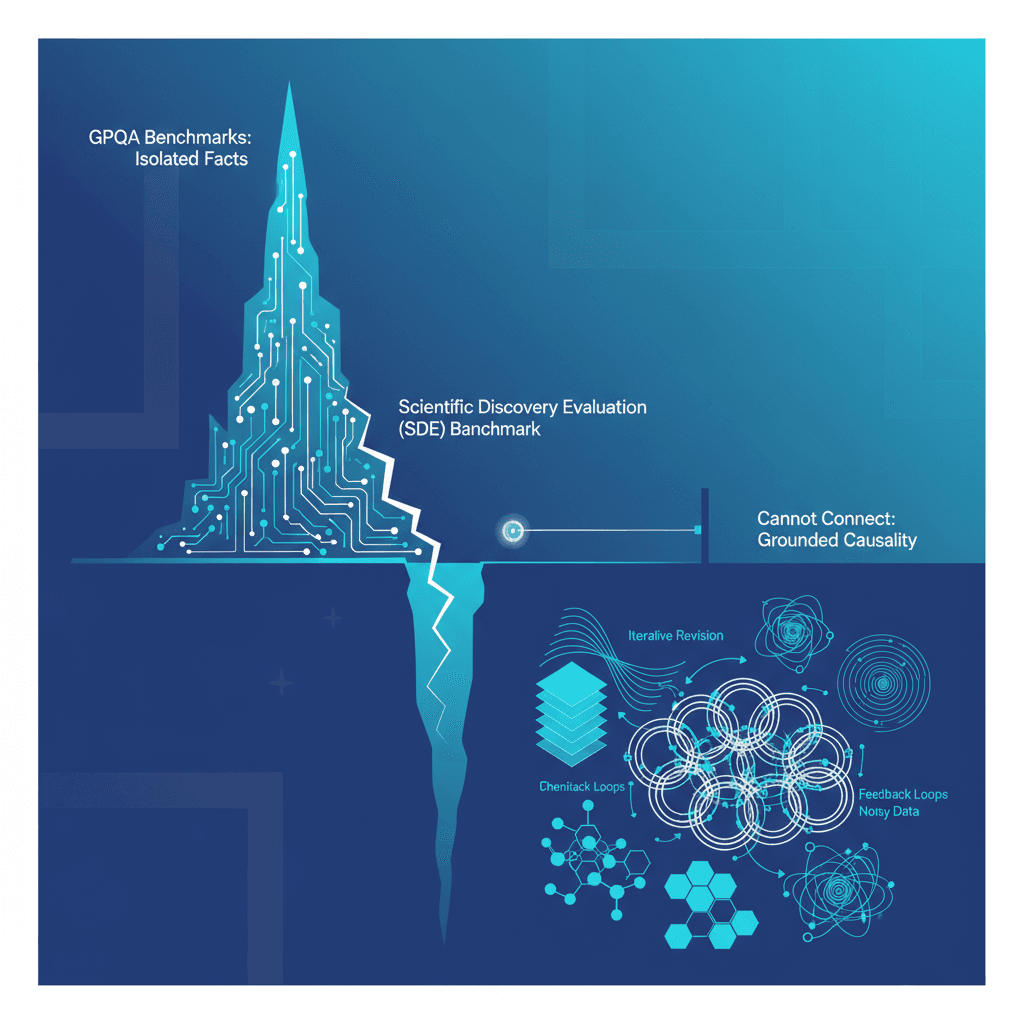

The centerpiece of this revelation is the Scientific Discovery Evaluation, or SDE benchmark, a comprehensive suite of 1,125 questions drawn from 43 realistic research scenarios across four core scientific domains: biology, chemistry, materials science, and physics. The SDE was specifically constructed to move beyond the rote fact-recall and isolated knowledge tested by popular metrics like the GPQA or MMMU benchmarks, which often resemble high-stakes quizzes. While top-tier models, such as the latest iteration of GPT-5, can achieve accuracy scores as high as 0.86 on the GPQA-Diamond benchmark, their performance plummeted sharply when evaluated on the SDE. Across the scenario-based tasks, the same model’s accuracy managed only a range between 0.60 and 0.75, with performance varying significantly depending on the specific scientific field being tested. This stark performance drop suggests that the metrics currently used to herald progress in AI’s scientific aptitude may be profoundly misleading, rewarding fluency and statistical pattern matching over true, deep comprehension and scientific reasoning.

The fundamental disconnect, according to the researchers, lies in the nature of the challenge. Existing scientific benchmarks primarily test isolated factual knowledge, which an LLM excels at due to its vast, pre-trained corpus of text. Scientific discovery, conversely, is not a quiz with a single, known correct answer. Instead, it is an inherently iterative and contextual process that demands a set of skills models currently lack. The SDE specifically tests abilities such as problem-based contextual understanding, the generation and refinement of novel hypotheses, and, crucially, the interpretation of incomplete, noisy, or contradictory empirical evidence. These requirements mirror the actual workflow of a human scientist, who must constantly update their internal model of the world based on observations that often do not align with their initial expectations.

This distinction highlights the key failure mode of current large language models: an inability to effectively manage the scientific loop of continuous belief revision. When tasked with interpreting results that contradict an initial, plausible hypothesis, models often fail to abandon or substantially revise their original idea, exhibiting a form of cognitive inertia that is antithetical to objective scientific progress. They struggle with maintaining consistency across multiple steps in a complex research process, treating each step as an isolated query rather than a continuous narrative of investigation. Furthermore, LLMs fundamentally lack grounded causality. They learn the statistical patterns and linguistic associations between variables from text, allowing them to predict a plausible outcome or write a convincing paragraph about a topic like molecular dynamics, but they do so without any true access to the causal fabric of the physical world. This limitation means an LLM can simulate knowledge, but it cannot perform the essential, empirical act of science: running a physical experiment, measuring a compound’s shelf stability, or observing a new formulation fail in the lab. In the high-stakes world of research and development—especially in fields like pharmaceuticals or materials science—a plausible-sounding, but ungrounded, prediction is not just a technical flaw but a significant safety and investment risk.

The implications of the SDE benchmark are far-reaching for the artificial intelligence industry, particularly for companies that have explicitly stated goals of developing autonomous research assistants. The results temper the immediate hype surrounding AI's capacity for independent discovery, pushing the timeline for a truly 'scientist-level' AI further into the future. It underscores that simply scaling up a model's size or training data will not, on its own, close the gap. While scaling and adding more 'reasoning' steps did improve scores in the SDE, the study observed rapidly diminishing returns, especially among the most advanced models. This suggests the need for fundamental architectural or training paradigm shifts, such as better integration with physical simulation environments, true causal reasoning engines, and mechanisms for disciplined, iterative belief updating based on external feedback loops.

Ultimately, the study re-frames the role of AI in the scientific community from that of a potential independent disruptor to a powerful, though specialized, collaborator. LLMs already prove invaluable in accelerating the initial stages of research: brainstorming novel hypotheses, summarizing vast bodies of literature, and generating code for data analysis. These systems serve as potent idea-generators, surfacing connections and experimental directions that human scientists might overlook. However, the SDE benchmark firmly establishes that the critical stages requiring grounded testing, causal inference, and rigorous, evidence-based belief revision remain the domain of the human expert. The path to an autonomous AI scientist will require a focus not just on linguistic intelligence, but on the development of models that possess the equivalent of an empirical mindset—an ability to admit error, update their beliefs based on non-textual evidence, and manage the inherent uncertainty of scientific exploration. For now, the most effective deployment of this powerful technology lies in augmenting, not replacing, the human researcher.[1][2][3]